Fixing Healthcare by Paying Doctors More

Either an incredibly self-serving or an idea just crazy enough to work. Only one way to find out!

If you bothered to come this far, chances you’re either intrigued by the notion above or angry enough to read further. Bear with me. While the idea of paying doctors more may seem extremely self-serving coming from a doctor (an Orthopedic Surgeon no less), there is some method to this proposed madness. Despite much discussion and various attempts to control healthcare costs and improve outcomes, success has proven elusive. Healthcare spending continues on an inexorable upward climb, outcomes aren’t getting much better, and alternative payment models have produced (at best) mixed results. While paying doctors more may seem like a dubious way to fix healthcare, the following is an attempt to explain how this controversial idea might actually work.

First, let’s look at healthcare spending. The good news (I guess) is that spending only increased by 2.7% in 2021 compared to 2020 which came in at a staggering 10.3% growth rate. The bad news is that this decline is more related to unusual pandemic-related activity and not necessarily any sustainable effort to control expenditures. Health spending represented 19.7% of GDP in 2020 but “dropped” to 18.3% in 2021. The Peterson Center on Healthcare and Kaiser Family Foundation provide a helpful National Health Spending Explorer interactive tool that is both fun and depressing to play around with. As we are all painfully aware, inflation-adjusted health expenditures have followed a trajectory that would be great for an investment portfolio but not so great for expenses.

Not surprisingly, the two biggest drivers of health expenditures are Hospitals and Physicians & Clinics. As a point of clarification, CMS defines the Physicians & Clinics category as “services provided in establishments operated by Doctors of Medicine (M.D.) and Doctors of Osteopathy (D.O.), outpatient care centers, plus the portion of medical laboratories services that are billed independently by the laboratories” as well as services billed by independently by doctors in the hospital setting or as part of government run programs such as the VA or DOD. Isolating these two categories produces the following graph:

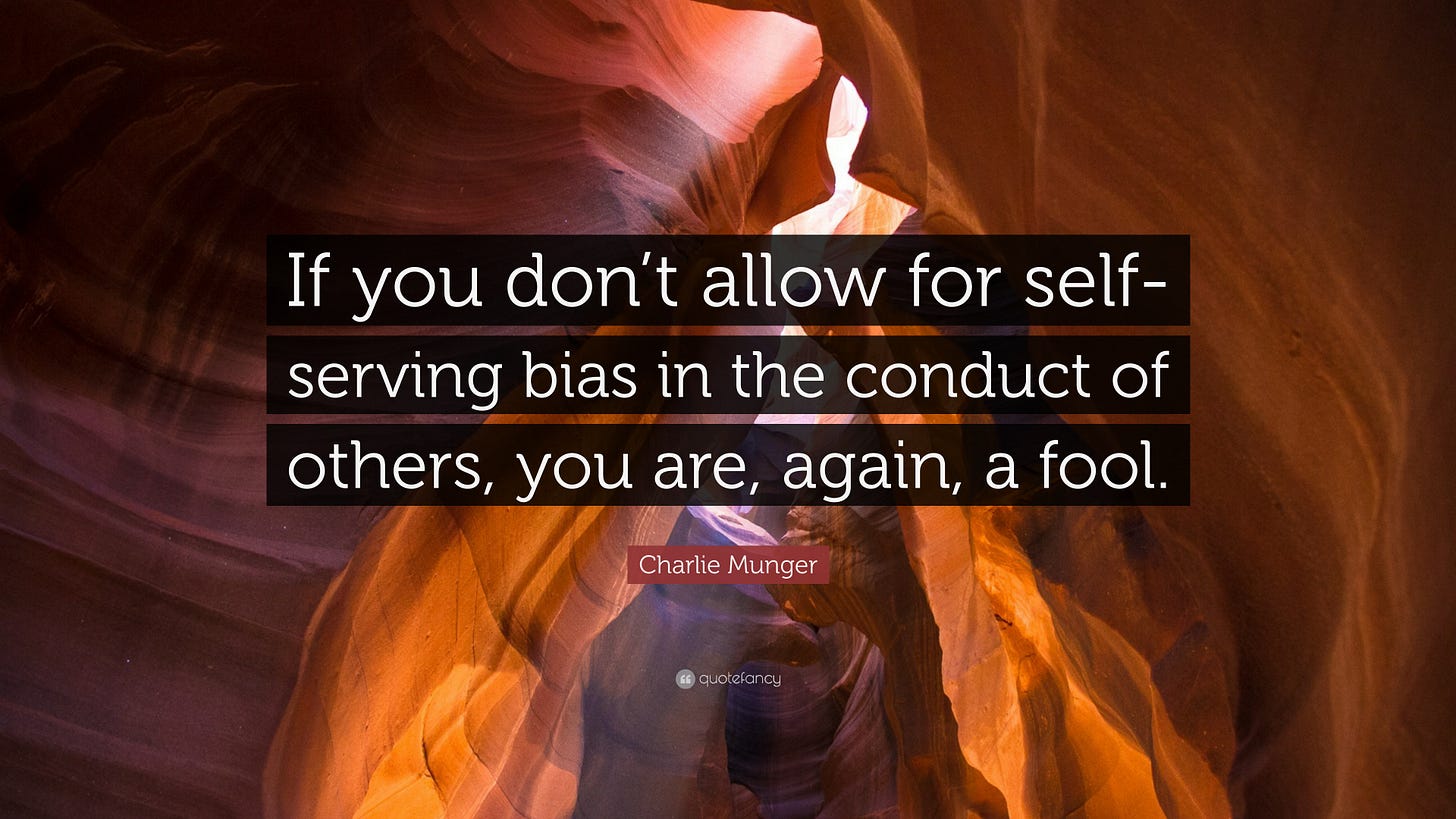

Hospital and P&C expenditures followed a relatively linear increase until about 2005 where the trend lines began to diverge with Hospital expenditures growing at a faster rate than P&C expenditures. Of course, one could go mad trying to sort out the differences between expenditures, payments, prices, and costs when it comes to healthcare economics. Tying one to the other is rarely a straightforward exercise, and parsing the data into meaningful insights can be tricky without falling into a finance rabbit hole that is beyond my area of expertise (I only got an executive MBA). A Health Affairs article from 2019 provides additional context, confirming that hospital prices grew substantially faster than physician prices for hospital-based care from 2007-2014.

In this study, hospital prices grew 42% for inpatient care while physician prices grew 18%. For hospital-based outpatient care, hospital prices went up 25% versus just 6% for physicians.

Similarly, an American College of Surgeons study found that the RVU conversion factor (which CMS uses to determine physician payments) actually declined in absolute value from 1998 to 2019, going from $36.6873 to $36.0391. (I hear Alfred E. Newman is on the 0.0001 cent piece). General inflation during that time period was over 50% meaning that, had the conversion factor kept up with inflation, the 2019 value would have been $57.60. The news gets worse for physicians as, after much wrangling, CMS moved forward with a 2% reduction in the conversion factor for 2023 (though this was reduced from an initially proposed 4.5% cut). Meanwhile, hospitals were scheduled to get a 3.2% increase in payments for inpatient care, a figure the American Hospital Association called “extremely concerning.” This number was ultimately increased to 4.3% for acute care hospitals engaging in meaningful use of EHRs. Per CMS, this increase represents the highest update in the last 25 years and is intended to offset the growth in compensation for hospital workers. (Sorry independent medical practices with growing office staff costs).

Before we move on, it’s worth mentioning a few other important components of healthcare costs in the US. Administrative costs make up a large portion of expenditures although discussing the growth of administrators v. physicians how touches the third rail.

We’ve all seen this graph on social media. It makes the rounds once or twice a month and spurs outrage and angst. As is frequently the case when the ‘Net gets sick of seeing the same memes over and over again, contrarian opinions have challenged the validity of this chart. In an in depth take down posted on Mother Jones, Kevin Drum suggests that the chart is a bit inaccurate. He admits that getting exact numbers is difficult but proposes that about 50-100% of healthcare growth can be reasonably attributed to administration. Whatever you believe about growth in administrative costs and its relation to growth in expenditures, most agree the US spends too much on healthcare administration.

Finally, let’s consider two other important components of healthcare costs: Big Pharma and Big Insurance. According to JAMA, large pharmaceutical companies posted a net income of $1.9 trillion from 2000 to 2018 on cumulative revenue of $11.5 trillion and gross profit of $8.6 trillion. The AARP found that, in every year from 2006 to 2020, the cost of prescription drugs increased at a much faster rate (4.7%) than general inflation (1.3%) from 2019 to 2020 — an over three times difference. Health insurance companies have also posted impressive profits in recent years. The pandemic years saw record breaking financial numbers for insurers as many patients either delayed care or simply couldn’t get treatment as hospitals and doctors’ offices went through several waves of shutdowns. Less care = fewer payments to doctors and hospitals. Insurers have also found a new revenue darling as Medicare Advantage plans now offer the highest gross margin per enrollee.

Peterson-KFF found that health insurance premium contributions by employers increased by 51% from 2008 to 2018 with a 67% increase in health costs incurred by families. Despite the increase in employer premium contributions, family out-of-pocket spending has increased over time, outstripping increases in worker’s wages.

Summarizing the data above, healthcare expenditures have increased, hospitals have generally fared better than physicians, administration, pharma, and insurers are significant cost drivers, and payment to physicians hasn’t kept up with inflation. One interesting thing to note, while the CF has remained flat (or declined compared to inflation), payments to physicians have increased in a linear fashion. How can this be? First, some ground rules. CF only represents the amount that CMS per relative value unit (RVU). Getting into the whole morass that is RVUs and the RUC is beyond the scope of this particular post. For simplicity's sake, let’s just assume that CF is a rough estimate of physician payments per service. In our oversimplified model, the fact that CF has remained constant means that physicians are being paid the same for each episode of service (in a fee-for-service model) today as they were 20 years ago in absolute dollars and significantly less in inflation-adjusted dollars.

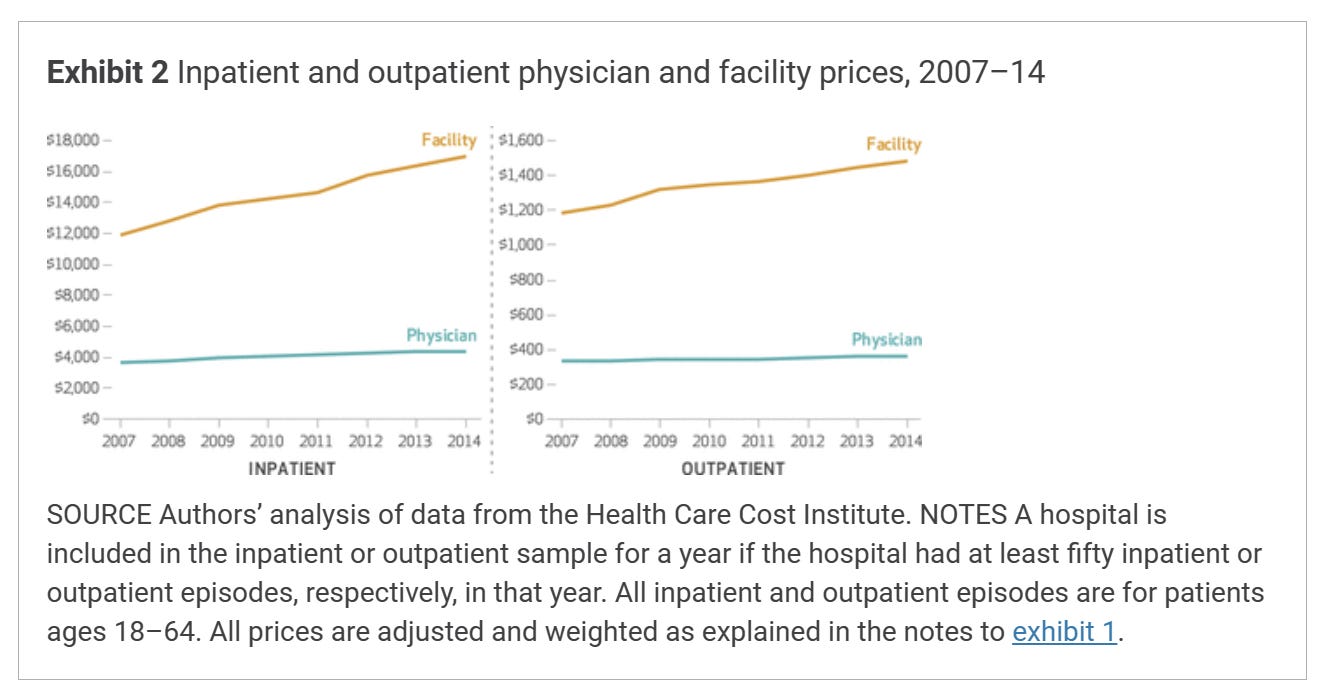

Here’s a real-world example from my specialty of joint replacement that bears this out. Mean Medicare reimbursement for hip and knee replacement experienced a 7.5% decline in constant dollars and a 14.9% inflation-adjusted decrease from 2012 to 2017. Interestingly, the volume of TJA procedures performed increased over that time period by 18.9%. I think it’s worth taking this example a step further for reasons that will be (hopefully) clear later. Let’s assume Surgeon A performed 300 joint replacements in 2012 with an average reimbursement of $1123 per case for total reimbursement of $336,900. By 2017, that same 300 cases reimbursed at $1038/case for a total reimbursement of $311,400 — or $291,558 in 2012 dollars. Taking into account inflation, the surgeon would have to bring in $359,655 in 2017 to match 2012’s reimbursement. At $1038/case, that’s about 346 cases or a 15% increase over 2012’s volume — not too far from the 18.9% increase in TJA volume observed during the study period. This brings us to the first potential explanation for increased physician payments despite flat/declining CF: physicians simply provided more services to offset declining fees.

Herein lies the crux of the argument against FFS — it incentivizes physicians to do more (often summarized as “quantity over quality”). This example provides insight as to why physicians do more — to offset declining reimbursement. Of course, if physicians were simply increasing volume to match inflation and declining reimbursement, inflation-adjusted payments would remain constant which isn’t the case here. Again, in our example the TJA volume increase was 5% greater than the minimum increase needed to offset inflation and reduced payments. To complicate matters more, physician payments do not necessarily directly correlate to physician salaries. For private practice physicians, overhead costs have to be considered. For employed physicians, salaries are tied to market dynamics as hospitals and health systems compete for their services.

The factors here are complex and represent yet another healthcare economics head scratcher. In general terms, running a practice has become increasingly expensive (about a 39% increase since 2001) and just becoming a physician comes with a significant debt load ($200k on average). One (imperfect) way to determine if increased physician payments have translated to higher pay is to look at compensation trends. According to a 2020 JAMA study of compensation trends between 2008 and 2017, PCPs saw an inflation-adjusted increase of 1.6% (about $4000) while specialists came in at 0.6% (about $2200). Modest numbers to be sure. While this doesn’t represent a decline, it suggests that physician payments are rising at a faster rate than physician compensation (and that the ACA wasn’t the boon to physician income some thought it might be).

Circling back to the original point, rising physician payments may be the result of a need to increase volume to maintain compensation levels in an era of declining reimbursement, increasing overhead, and sky-high medical school debt. Here comes the self-serving part: what if most physicians are incentivized to do more in FFS not out of abject greed but simply to tread water in an increasingly unfavorable economic environment? Doing more has resulted in more payments but relatively flat compensation. Essentially, physicians are working harder to take home the same pay. Critics are quick to point out that FFS drives volume but rarely consider what that means in practically. Hearts don’t catheterize or stent themselves any more than hips and knees are replaced with a simple wave of the hand. Unless you’re engaging in outright fraud, doing more means putting in the work. Factor in that the population is becoming less healthy and more complex, administrative burden is increasing, and staffing issues abound, and you get a recipe for burnout, decreased job satisfaction, and a suicide rate double that of the general population.

Here’s another self-serving thought: could a corollary of the “FFS rewards volume” argument be that paying doctors more would incentivize them to do less? Who would be against working smarter not harder? Opponents frequently point out that FFS leads to a significant amount of unnecessary, low-value care. Beyond the cost of paying for the service itself, increasing volume has downstream effects that serve as a force multiplier to costs: more complications, more diagnostic tests, more post-acute care, more readmissions, more ER visits…the list goes on. In the primary care setting, the need to see more office visits means less time to spend with each patient. PCPs are struggling to keep up with documentation requirements, administrative tasks, and pre-authorization requests at the expense of patient care. Delivering high quality, high value primary care requires time and effort PCPs simply don’t have. Advanced primary care models have had some success adopting a patient-centered, medical home model. But most rely on cost savings in a value-based care model (mostly Medicare Advantage) and few, if any, have proven to be profitable.

Declining reimbursement has had another unintended consequence — increased consolidation. Unable or unwilling to continue the struggle of keeping their heads above water, physicians have left private practice in droves. We are at a point where more physicians are employed than independent. Despite arguments to the contrary, consolidation is a major driving force behind increasing costs. It also contributes to burnout through loss of autonomy. Given the choice, I suspect many physicians would prefer to remain independent if doing so was financially viable. Increasing payments to physicians could achieve this goal and reverse the consolidation trend.

The widely accepted solution to the cost problem is value-based care. In theory, VBC rewards quality not volume and disincentivizes expensive, low-quality treatment. Early VBC programs provided upside risk allowing physicians to participate in shared savings without penalties for poor performance. Going forward, it’s likely that most VBC arrangements will include downside risk — the prospect of owing money back (losing money) for subpar outcomes. CMS has expressed a desire to move all Medicare/Medicaid participants to some form of VBC in the next several years. For their part, commercial payors have talked a good game but have yet to enact widespread alternative payment models. They love the idea of shifting risk to providers though. Not only have VBC programs largely failed to achieve meaningful cost savings or reductions in spending, but it also seems naive to think physicians are ultimately going to benefit from these programs. Most physicians are skeptical. Such programs are complicated to administer (with their own associated costs) and are seen as placing another barrier between doctor and patient.

I realize the suggestion of paying physicians more may elicit eye-rolling. American doctors are paid more than their counterparts in other parts of the world. Physician compensation is another complex, hot button topic that deserves a post of its own. I also realize that, coming from a specialist who is amongst the most well-reimbursed of all physicians, such a suggestion seems dubious. If we are going to consider paying physicians more, we should absolutely start with areas of biggest need: primary care (including Pediatrics) and mental health. One argument is that payments should be shifted from procedure-based specialties to primary care. I think this is a false choice. Doing so may simply drive more utilization of high-cost services which would be counterproductive. There are other ways procedural specialists can capture additional revenue including ASC ownership and offering ancillary services. Eliminating the ban on physician-owned hospitals could also help achieve this goal.

The above proposal to pay physicians more has several potential flaws. First, some have become accustomed to performing a high volume of services. That ship has sailed and may never return to harbor. Increasing payment may not reduce utilization as intended which would worsen the problem rather than help solve it. But, given the choice, I think many physicians would take the tradeoff of doing less to make the same. There is also the concern that, if physicians do less, access to care will become worse. A couple of thoughts there. First, this is where digital health, innovative care delivery models, and patient engagement platforms can play a role. Adoption among physicians has been slow in part because it’s difficult to prove return on investment. No matter how great your tool is, if it costs money, it’s hard to gain traction. However, physicians may be more receptive of these tools if they were less threatened by their impact on practice economics. Secondly, increasing payments may make more physicians receptive to accepting Medicare/Medicaid. As it stands, Medicaid patients already struggle with access. As CMS payments continue to decrease, more and more physicians are questioning whether they should continue to participate in the Medicare program. Finally, improved support of primary care would drive better prevention and management of chronic conditions. In turn, there would be less need for cost-drivers like hospitalizations and specialty care.

There are other arguments to be had here. Physicians should just accept lower payments — they’re still better off than most. We could increase compensation by reducing the costs of medical education and practice. Increasing payments may do absolutely nothing to improve the quality of care nor decrease overall costs. I have a lot more thoughts here that are probably worth a follow up post. In the meantime, I invite counterarguments and thoughtful criticism.

The thesis here is simple if not provocative: decreased physician payments have paradoxically increased the cost of care by driving volume and consolidation. This in turn reduces the quality of care (more patients to see, less time to see them) and creates a downstream multiplier effect that further increases costs. If FFS incentivizes more care (some of which is unnecessary), increasing payments negates some of that incentive. So far, we’ve twisted ourselves in knots trying to achieve better value in healthcare without much demonstrable success. Maybe the reason we can’t find value in healthcare is because we’ve devalued those who provide it.