By now, the challenges facing musculoskeletal care delivery are well chronicled. Treatment of MSK conditions costs the government and employers a lot of money, care quality is highly variable, and — so the narrative goes — there is a lot of expensive, low value, unnecessary care. The pervasive fee-for-service system favors tests and procedures without providing a mechanism to reward conservative treatment. Whether it’s volume over value or quantity over quality, criticisms of the current system are common refrains. If the axiom that incentives drive behavior holds true, how do you convince Orthopedic Surgeons to put down their scalpels and pick up their physical therapy referrals? The assumption here is that surgeons just want to operate and are financially driven to eschew non-surgical care. Is this assumption grounded in cynicism or reality? The situation is complex, and the truth lies somewhere in between. But various attempts to solve this conundrum have failed to produce sustainable results.

Contrary to popular belief, Orthopods have been on the forefront of value-based care, more so than almost any other medical specialty. Joint replacement surgeons have worked with CMS to design and implement programs such as the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) and Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR). Taken as a whole, these programs have been successful in reducing costs without sacrificing care quality. Furthermore, there’s evidence that concerns about cherry-picking and lemon-dropping never manifested in access restrictions. That’s the good news. The bad news is that such programs are solely tied to surgical episodes. While they help reduce costs associated with hip and knee procedures, they do little to address non-surgical care. This shortcoming limits the impact of these programs and prevents realization of comprehensive, integrated value-based MSK care. Attrition is another major problem with current MSK-focused VBC programs. Surgical bundle target prices shift lower, maximum efficiency is reached, margins compress, and upside risk flips to downside risk — the proverbial race-to-the-bottom. Rather than pay money back to the government, providers simply leave these programs and return to traditional FFS. (The Rothman Institute at Thomas Jefferson University is a perfect case study of this phenomenon.)

CMS plans to sunset both the CJR and BPCI (now BPCI Advanced) programs by the end of 2025. Whether or not these programs were successful depends on your expectations, definition of success, level of patience, biases, and point of view. Again, both generally achieved their goals of reduced costs without compromise in care quality, outcomes, or access. Participation in these programs led to valuable lessons regarding health optimization prior to surgery, mechanisms to reduce readmissions, and avoidance of expensive post-acute care (the biggest cost driver). However, adjusted payments made to hospitals during the pandemic wiped out CJR savings and turned the program into a net loss for CMS. While CJR is a mandatory program, BPCI is not. As discussed earlier, downward pressure on target prices and unfavorable program changes between original BPCI and its successor BPCI-A have led to significant attrition. What good is a voluntary program that no one volunteers for?

CMS and CMMI clearly remain committed to value-based care, particularly as it pertains to MSK. The expectation is that CJR and BPCI will be replaced by some other form of accountable care. The other expectation (fear?) is that participation will be mandatory. Exactly what this new program will look like hasn’t come fully into focus. CMMI may have tipped its hand a bit with the recently announced “Making Care Primary” program — an attempt to further align PCP and specialists while supporting “advanced primary care services.” I’ve written previously about this program and what it might mean for specialty care delivery. Briefly, “Making Care Primary” sounds an awful lot like an attempt to incentivize a PCP-led medical home approach that rewards them for taking a more active role in care coordination. Reading between the lines, CMS is pushing primary care as the steward and gatekeeper of specialty services. Interestingly, this approach isn’t that different from what’s happening in VC (now Big Retail)-backed alternative primary care models such as Oak Street Health and the Iora/One Medical (although those companies rely on Medicare Advantage rather than Traditional Medicare).

Putting it all together, the evolution of VBC MSK will be some form of comprehensive, longitudinal, whole person care that encompasses the entire patient journey — also called “condition-specific” VBC. Here the bundle or capitated payment is tied to a diagnosis, not a procedure. In theory, condition-specific VBC is more effective at driving value across the care continuum by finally solving the conundrum of how to incentivize conservative over aggressive and value over volume. The elusive “quality over quantity” promise can finally be realized, and Orthopedic Surgeons can finally be enticed not to operate (if you’re so inclined to believe this narrative).

In this new model of care, procedures will be nested within the larger care pathway rather than discreet surgical episodes. As a corollary, this approach opens the management of MSK conditions to whoever is willing to accept the upside and downside risk that comes with participating in the program. Again, CMS seems to be prodding PCPs to step up to the plate. However, anyone who wants to take the lead on full-service management of MSK conditions (with an emphasis on conservative, longitudinal treatment) could theoretically participate — startups, APC companies, Physical Therapists, and even Orthopedic Surgeons.

The crux is that success in such a program will require a willingness to engage in comprehensive chronic care management including behavioral and mental health, management of medical co-morbidities such as diabetes and obesity, and robust care coordination. Orthopedic Surgeons (and other MSK-focused specialists) are best suited to evaluate and manage bone, muscle, and joint problems, but few would consider themselves experts (or willing participants) in these other aspects of a condition-specific approach. The converse is that PCPs are better suited for CCM but less suited for specialist-level MSK expertise or perioperative management of nested surgical bundles. So how best to create a program that achieves these goals and makes sure the patient gets appropriate care?

There are a few potential approaches. First, Orthopedic Surgeons could bring CCM capabilities in house or, conversely, PCPs could do the same for MSK condition management. Shifting payment models and financial incentives could make doing so attractive from a business standpoint. Clinically, success in these programs would rely on getting both sides of the equation right — especially if participation is mandatory. Although CJR and BPCI weren’t quite as comprehensive, many who participated in these programs hired nurse navigators or other allied professionals to ensure success.

Condition-specific VBC also creates an opportunity for risk-bearing third parties such as conveners or care navigators who bridge the gap between PCPs and specialists. The key here is making sure each side sees value in program participation. Thoughtfully implemented programs allow PCPs to reap the benefits of upside risk and ensure their patients get appropriate specialty care without forcing them beyond their comfort zones. For specialists, proving quality, cost effectiveness, and superior outcomes can be a conduit to more favorable payments from nested surgical bundles. The program could also provide a pipeline of patients who have been appropriately managed and optimized prior to referral to further streamline processes.

While a condition-specific approach may address the shortcomings of current MSK treatment (including FFS and existing VBC programs), it’s not without its own potential issues. As I’ve often argued, no payment system is unexploitable, and any incentive can be perverted. Forcing a patient with end stage arthritis, significant pain, and profound functional limitations into weeks or months of conservative treatment to save money in a bundle (or, in the case of MSK startups, to prove ROI) is low value care. Full stop. Pointlessly delaying definitive treatment is not equivalent to avoiding unnecessary surgeries and procedures. Doing so almost certainly costs the system more money in the long run. Condition-specific treatment should incentivize the right care, not define success by the amount of short term, PMPM savings. Other challenges of condition-based VBC include how to define conditions, what to do when diagnoses overlap, and when/how to set a beginning and end to the bundle or capitated period.

Discussions around payment models, FFS v. VBC, misaligned incentives and the like always bring me to the same conclusion. We struggle to gain traction and make progress because leveraging payment method is a poor mechanism for driving high quality, high value care. If we assume the worst and design systems with the intent of legislating good behavior, we’ve probably already lost. Are there knife-happy surgeons out there? Sure. Are there those who repeatedly take advantage of the gray areas between aggressive and fraudulent? Yep. Does FFS drive overutilization? No doubt. Are these behaviors pervasive, unavoidable, and unsolvable? On that, I’m not so sure. Quality and value will always be the byproducts of good care. They cannot be willed into existence by carrots and sticks. Bad actors will be bad actors. Their methods will simply change along with the shifting incentives.

What’s the solution? Trust but verify. Rather than designing systems that force certain behavior, why not reward those that reliably and transparently demonstrate value? The current game of distrust, false collaboration, and goalpost shifting isn’t getting us anywhere. We are starting to see this play out through direct contracting, and I believe this approach will evolve and become more widespread. There is plenty of room to integrate primary and specialty care without pitting the two against each other in a monetized fight for who’s going to play gatekeeper. The promise of clinically integrated networks, multispecialty clinics, integrated delivery networks, consolidated health systems, etc. is to deliver value through tightly connected processes. Why have so many of these efforts failed to realize their potential?

I’ll put yet another plug in for a ground up, hybrid, truly integrated next generation MSK approach I’ve written about often. Perhaps the biggest barriers here are breaking down silos and having centralized ownership of the care journey. Incentives are hard to align, and fragmentation remains the state of play. We’ve blown billions of dollars — taxpayer, VC, PE, employer, payor, provider, patient dollars or otherwise — without much to show for it. If CMS (or anyone else) really wants to innovate here, why not spend some time and money trying something completely different rather than retrofitting processes onto a broken system?

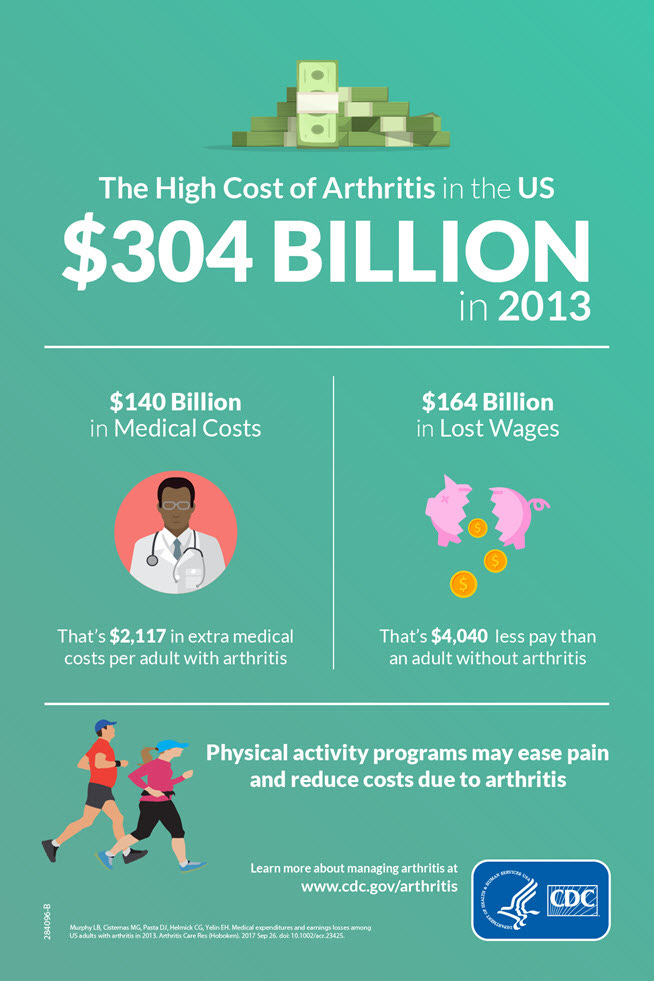

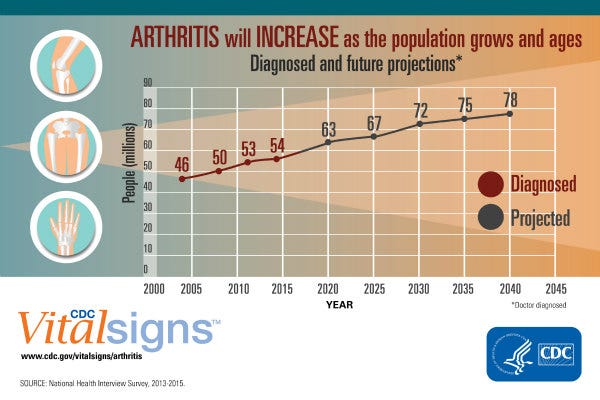

Finally, we need to accept that demand for MSK services is going to explode, driven by an aging population, the obesity epidemic, and the “silent” epidemic of early onset hip and knee arthritis (which may be driven by year-round youth sports). If anyone out there is doing unnecessary hip and knee replacements, I have one simple question: Why? There’s going to be plenty of cases to go around. No matter how efficient and value-driven we are, total costs are going to rise, and demand is going to outstrip supply. There is a place for prevention, education, and engagement here if we can figure out how to incentivize and reward it. GLP-1 agonists hold the promise of reducing weight-related joint degeneration (as well as making eventual procedures safer). Remote therapeutic monitoring, provided CMS continues to support its use, offers the ability to better manage MSK conditions longitudinally while preserving access and lowering costs. The shift to lower cost outpatient centers and ASC will save money as well. All levers will need pulling if we are to stem the tide, and they’ll be easier to pull if attached to the same machine.

Full credit should be given to the team at the UT Austin Musculoskeletal Institute for being on the forefront of value-focused MSK care. For an excellent, in-depth review of MSK alternative payments models, I highly recommend this whitepaper and its companion piece written by Drs. Benjamin Kopp, Kevin Bozic, and Karl Koenig from the Dell Medical School at UT-Austin. Dr. Bozic and his team have led the way on MSK APMs including the concept of condition-specific bundles.

Hey, Ben. I follow your superb posts closely and it is clear that our perspectives are aligned. Would love to chat more about this one in particular. I'm an arthroplasty surgeon as well. I've been a staunch advocate for Porter and Teisberg's Integrated Practice Unit concept around MSK since I read their book 15 years ago (on Kevin's recommendation). Orthopedic surgeons should be MSK mentors to our PCP colleagues. Actually, tried 3x to set one up with our community PCPs - each went down in smoke. Timing wasn't right and incentives were completely misaligned (there was no financial downside risk for non-participation in the program). If you feel up to it, connect on steve.schutzer@gmail.com. Happy New Year.